A Political Earthquake?

The dust has settled after Japan’s ruling coalition has clearly lost its long-standing electoral lead in the House of Representatives and, with it, its majority. By now, major news outlets have weighed in on how this will impact Japan and the broader region. Some sources describe the “faltering” of Japan’s “indispensable party” (2024/10/28 NYT, the title was changed later on) or declare that this “seismic” election is plunging Asia’s “most stable democracy into chaos” (2024/10/28 NYT). Others argue, “this result is not good for Japan” (2024/10/28 SZ). But is this truly the case? Is the electoral loss of Japan’s conservative party as alarming as media pundits make it out to be?

In my opinion, yes and no. Let me break down why changes to the political landscape are on the horizon, yet these calls might be a bit hasty. Over the past three months, I’ve had the opportunity to conduct fieldwork across various prefectures in Japan as part of my ongoing research on rural communities’ resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic. These conversations gave me valuable insight into political sentiment — sometimes firsthand expressions of visible discontent with politics.

Before diving in, let me clarify what this post aims to do. As I’ve mentioned before, this blog offers a light political and sociological take on current events in Japan. So, while this analysis is grounded in my experiences, it does not come close to the rigorous standards of a peer-reviewed article. Consider this an essay on my perspective based on field observations.

The Big Winner: No One

So, is this really the pivotal shift some pundits are proclaiming? Is the LDP truly in decline, bringing Japan’s stability down with it? Let’s start with the basics. After Fumio Kishida, Japan’s most unpopular prime minister, resigned this summer, Shigeru Ishiba won the LDP presidency in a competitive election, following weeks of intra-party conflict. Without fully securing party support, Ishiba called for a snap election. He even revoked recognition of several party members — many tied to former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s influential ultra-conservative faction — over secret political donations (referred to in the media as the uragane mondai). It seems Ishiba thought this swift political root canal would convince voters in an exceptionally short, three-week campaign period.

Obviously, this plan did not work. The LDP lost, securing only 191 seats of the 233 needed, while its biggest competitor the Rikken Minshutō (Constitutional Democratic Party, CDP) was able to gain 50, securing 148 seats. No party seems to have secured a clear mandate from the electorate. This introduces the necessity to explore new majority structures by forming a coalition government — with or without the LDP — presenting an extremely complex situation to Ishiba (also see 2024/10/28 Zappa, Marco).

The LDP‘s loss is even more significant when taking into account the low voter turnout, which has so far greatly benefitted them since 2012. Even with only about 53% of voters showing up, the LDP was not able to keep a simple majority. Even among the people that do vote, they lost their footing. Moreover, even in traditionally conservative areas in the country side, voters seems to have turned their back on them. This signals the real „seismic“ shift.

It seems like the discontent with the LDP has reached a boiling point. Which to me feels reminiscent of the post-Angela-Merkel CDU/CSU in Germany or post-Brexit Tories, where long-ruling conservative parties faced rejection amid high-profile scandals.1

The Societal Basis of Low Voter Turnout

First, I want to have a quick look at the electorate. I’ll leave the in-depth analysis to colleagues specializing in voter behavior, but here is what I observed:

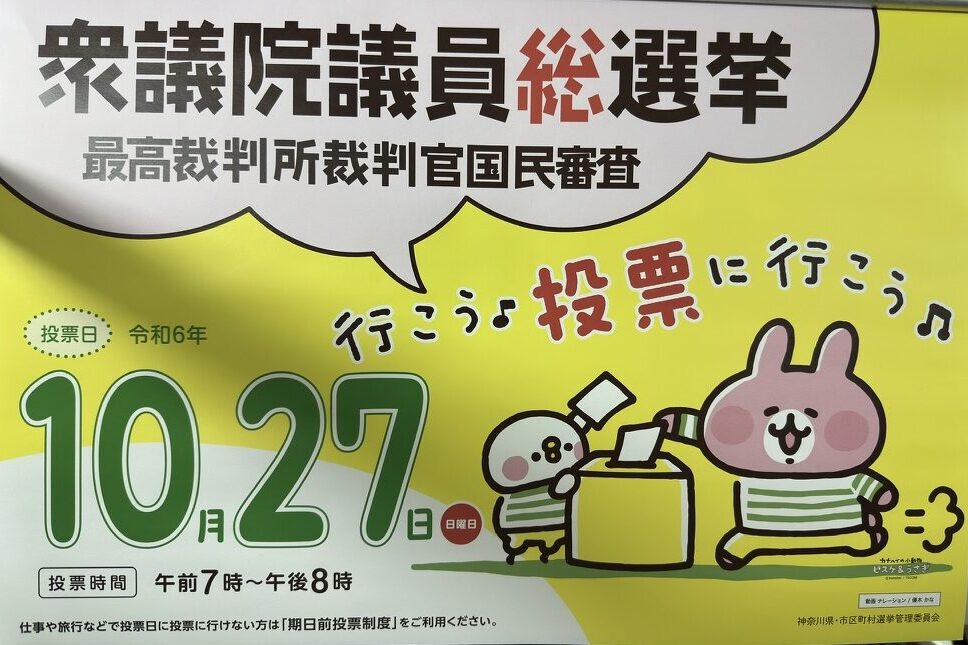

Giving the conversations I’ve had, I was surprised by the low turnout. Many people I talked to seemed not only frustrated with the LDP but also willing to show them the door. Furthermore, election information was widely available, e.g. this ad in a train (see Figure 1), that informs on the upcoming election. Also on LINE (Japan‘s “everything app”, that 80% of the population use) you could easily access information about every candidate‘s position on important issues (see Figure 2).

Yet, voter turnout did not increase significantly. While it has been slowly growing over the last years, were talking about minuscule amounts. In my observation, the lack of available information does not seem to be a main driver of disenfranchisment. Instead frustration with the LDP, combined with disillusionment with the political landscape and a lack of enthusiasm about alternatives seem to be a main factor driving people into political apathy.

This sentiment became clear to me in a recent encounter with an elderly citizen in rural Kyushu. When I mentioned my research on politics, he openly expressed disgust, remarking, “Stay away from this dirty stuff.” Yet, despite his disapproval, he was well-informed and concerned about global and domestic matters — a sign that it’s not the politics but the political landscape that voters are disillusioned with.

This disillusionment appears across age groups. Young people, for instance, often express political apathy, with comments like, “Nothing changes anyway, so why bother?” While observing a polling station in Tokyo, I overheard two young women passing by, one saying, “Election, really?” Although Japan’s youth aren’t necessarily uninterested, voting doesn’t seem to resonate with them. My colleagues at LMU’s Japan-Center are doing cutting-edge research on the youths complex relationship with politics right now, so go check them out!

Some voters find the process of voting itself a hassle. At one early voting site I visited, there were more election workers than voters during after-work hours (Figure 3), which should be a great occasion to hand in your vote on your way back home. Furthermore, there was only one early voting site in the entire district! However, for many residents the access to it is less than optimal.

Sometimes I was confronted with the sentiment, that voting is just too bothersome. In Japan’s time-constrained work culture, limited early voting access and long lines on election day may deter people. Individual time constraints are a significant hurdle to political participation. Particularly if they’re politically disillusioned and also exhausted from work.

Where Do We Go from Here: Two Scenarios

Now, what does this mean for the political system, when voters can’t even be motivated to show up after one of the biggest political scandals in recent years, alongside lingering dissatisfaction over the sluggish economic recovery post-Covid-19 and the rising cost of living? And what does this mean for the LDP? Is the stability of Japan’s democracy really tied to the the “indispensable” LDP, and are both in decline?

From my perspective, the ongoing process of forming a new government doesn’t seem as unstable as some commentators suggest. That said, I’m open to being proven wrong — and I look forward to analyzing any outcome! A coalition now seems the most likely path forward, unless the LDP refuses to grant the Kokumin Minshutō (Democratic Party For the People, DPP) a few key legislative concessions (2024/10/31 Asahi).

It seems unlikely that Ishiba would risk his legacy by going down as one of the LDP’s biggest losers — by doing so becoming Japan’s Armin Laschet — which gives the considerable leverage to the DPP. Furthermore, Ishiba will be threatened by his ultra-conservative peers if he’s unable to secure power, which makes him pushing for a quick agreement more likely.

Two scenarios seem possible, assuming the LDP manages to stay in power, whether as a minority government or through a coalition with the support (or toleration) of the DPP and Komeito.

Let’s take a closer look at the first scenario, which hinges on one main question: Can the LDP convince voters that, despite their extensive history of corruption cases, the uragane mondai was just an isolated issue that won’t reoccur? Success in this regard depends heavily on whether Ishiba (or a potential successor) can swiftly eliminate doubts about the party’s stance on corruption. If they can manage this effectively, it’s plausible that they might recapture voters who strayed to the CDP this election, as long as the non-voting block cannot be motivated to show up.

Why? Because, if we examine this year’s election campaigns, none of the opposition parties have, in my opinion, proposed a compelling vision for Japan’s future. From the right-wing Nippon Ishin no Kai (which translates to “Association for the Restauration of Japan”, JIP) to the Kyōsantō (Communist Party, CP), they’ve all essentially run on some variation of “we’re not the LDP, so please vote for us” and calls to “get these old geezers out.” JIP, for example, centered its campaign on it‘s slogan “let’s smash the old politics.” Its short TV spots, while provocative, did not offer a substantial roadmap for Japan’s future.

Now let’s turn to the second scenario: the LDP fails to dispel doubts about its integrity and continues to govern as a minority or coalition government without widespread public support. This path presents significant challenges for Japan’s political landscape, largely depending on whether individual politicians prioritize institutional stability over party power.

What does that mean in practical terms? In this scenario, Japan’s already existing — but so far mostly unsuccessful — “populist”2 parties could start attracting support from dissatisfied voters who feel “disgusted” by centrist parties. Still, with trust in the centrist option waning, these parties might start to become more appealing to disaffected voters, who don not resign themselves to political apathy.

Now, here lies the question at heart of Japans political stability: Will populist parties be able to exploit the now clear gaps in the voting market? In certain regions, such as Okinawa (All-Okinawa, also see Ken Hijino and Gabriele Vogt 2019) and Kansai (JIP), we’ve already seen some parties and movements succeed in capitalizing on local discontent, but not on the national level.

As long as this question is not answered, speaking of instability seems far-fetched. If these parties remain unable to build broader, cross-regional support, it’s unlikely that Japan’s democracy will be thrown into chaos. Yet, if a potent right-wing challenger might emerge in the near future, this might embolden the ultra-conservative faction inside the LDP to take over control and put the party on a similar trajectory as the German CDU or the Tories.

However, for now a coalition government is unlikely to accelerate Japan’s descent into „chaos“. The notion that one party is indispensable reflects more of a lack of political creativity than an actual threat to Japanese stability. Coalitions are an essential feature of parliamentary democratic systems, and recent examples, such as Poland, have demonstrated how effective they can be after years of unchanging governance.

Is This the End of Japanese Stability?

Populist parties like the JIP, Sanseitō (Do it Yourself Party or literally „Participation Party“, DIY), and Reiwa Shinsengumi would need to significantly enhance their ability to broaden their electoral base — not only targeting voters outside of their home regions but also mobilizing the non-voters — to cause any meaningful shift away from the conservative center. Currently, this prospect seems unlikely. However, based on my conversations with people across Japan, there is a growing sense of economic misery and frustration with the political process that could serve as fertile ground for such a shift in the future.

So, is the LDP experiencing its downfall? While the corruption scandals have temporarily impacted their standing in this election, the political landscape in Japan could just as quickly shift back in their favor. Centrist voters who shifted to the opposition in this election could potentially be won back if the LDP can decisively resolve the ongoing corruption scandals. This election cycle, the opposition focused primarily on the LDP’s corruption, neglecting to prominently present long-term legislative topics that might resonate more deeply with voters — despite there being plenty of.

If the CDP is unable to stop a LDP coaltion or minority government, it might prove difficult for them to bind centrist voters to them. Additionally, the opposition appears to be struggling to effectively engage the non-voting bloc, making their success largely dependent on centrist voters oscillating between the LDP and the CDP. Without a compelling alternative, these voters may remain disengaged, allowing the LDP a path to reclaim their support.

However, if the LDP fails to win back these voters, the landscape may become ripe for populist parties to capitalize on the discontent with the government. The ultra-conservative factions inside the LDP might act on this chance for a power play and send the party further to the right. For now, it remains to be seen how the political dynamics will evolve. Yet, for now Japanese democracy remains stable, but has to adjust to new political realities.

- However, it is important to say that these parties are quite different – for example the post-Merkel CDU first leaned centrist and only after loosing it’s pivotal election shifted to the right. Traditonally the LDP has been covering a considerably wide range of voters, but has already shifted significantly to the right under Abe. Also both German and Japanese governments haven’t been nearly as turbulent as the many different Tory governments of the last decade. ↩︎

- The term “populism” must be used carefully in Japan. Some parties’ mirror the populistic rhethoric of political parties elsewhere, yet they lack widespread popular support. This begs the question, what is populism without the populus? Anyhow, this topic is an ongoing debate among political scientist focused on Japan. ↩︎